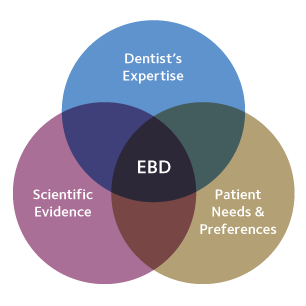

The American Dental Association (ADA) defines Evidence-Based Dentistry as “an approach to oral healthcare that requires the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence, relating to the patient’s oral and medical condition and history, with the dentist’s clinical expertise and the patient’s treatment needs and preferences.”

The EBD process has five steps:

The EBD process has five steps:

ASK - form a clinical question to solve a patient problem.

ACQUIRE - the best available evidence.

APPRAISE - the evidence. Is the evidence valid? Will it help my patient?

ACT - how will the practitioner integrate new evidence with the patient's support?

ASSESS - how did the EBD process help their patient and their practice?

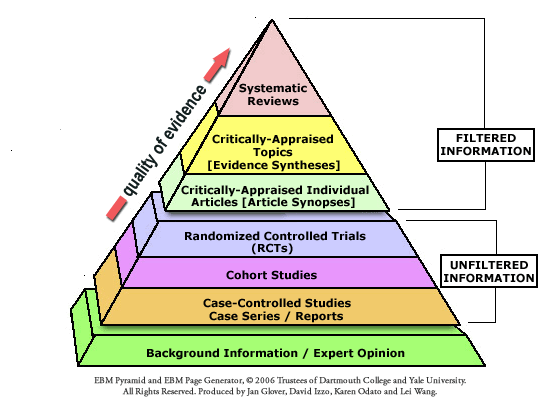

A pyramid is a way of visualizing levels of evidence and is related to research study design.

A pyramid is a way of visualizing levels of evidence and is related to research study design.At a basic level, Filtered information are information types that have been synthesized and interpreted for the reader. The ADA EBD site, the Cochrane Library, and systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in journal literature (and searched in PubMed/MEDLINE) are examples of filtered information.

Unfiltered information is usually journal literature, but can also include expert opinion, textbooks and other available sources that require the reader to find, critically appraise, synthesize, and interpret the evidence before considering to apply it to a patient's problem. PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library are examples of sources of unfiltered information.

The evidence pyramid tends to equate the hierarchy of research study design in a source with quality and validity (top of the pyramid is "good," while the bottom is less reliable). While this is often misinterpreted to mean searchers should only seek out systematic reviews and clinical trials as the most esteemed research designs, the reality is the study design should be matched to the clinical question, and searchers should strive to find the best available evidence.

Review the series of brief articles by Levin, listed below, to learn more about study designs.

Augusta University users can read the Levin articles by:

Levin KA. Study design I. Evid Based Dent 2005;6(3):78-9.

Levin KA. Study design II. Issues of chance, bias, confounding and contamination. Evid Based Dent 2005;6(4):102-3.

Levin KA. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evid Based Dent 2006;7(1):24-5.

Levin KA. Study design IV. Cohort studies. Evid Based Dent 2006;7(2):51-2.

Levin KA. Study design V. Case-control studies. Evid Based Dent 2006;7(3):83-4.

Levin KA. Study design VI - Ecological studies. Evid Based Dent 2006;7(4):108.

Levin KA. Study design VII. Randomised controlled trials. Evid Based Dent 2007;8(1):22-3.

CASP maintains downloadable Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists for many study designs to help make sense of a journal article.

Two articles by Sutherland are also useful. Paste the citation into the PubMed search box to retrieve the PubMed record and link to the full-text document:

Sutherland SE. Evidence-based dentistry: Part V. Critical appraisal of the dental literature: papers about therapy. J Can Dent Assoc 2001;67(8):442-5.

Sutherland SE. Evidence-based dentistry: Part VI. Critical appraisal of the dental literature: papers about diagnosis, etiology and prognosis. J Can Dent Assoc 2001;67(10):582-5.